Comment: The Scottish example or how respecting national values could project a dignified image of Romania

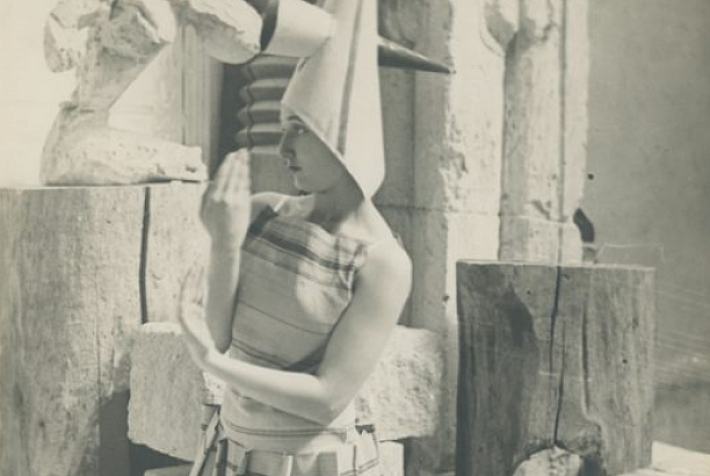

One topic endlessly debated in Romania some time ago was the country brand. Some may ask why write about it now, when the news of the day might be more pressing? I got my inspiration from the two close and similar events, the Romanian national poet Mihai Eminescu’s day and the Scottish national poet Robert Burns’ day. January 15 is the day when Romania celebrates the birth of its national poet Mihai Eminescu, while January 25 is the birthday of Scottish national poet Robert Burns. Eminescu (in opening picture) was born in 1850, Burns (picture below), a century before, in 1759.

As a poetry lover I read some of their poems but, I don’t think I have the professional expertise to analyze their work, so I will stick to what I can analyses: how the two peoples – Romanian and Scottish – celebrate a similar event.

In current times in Romania, the national poet is a topic of debate, especially due to the different political regimes which

have used his works on their own interests. Now in so-called democracic times, many people appreciate that they have the duty and the right to tell/write what they want about Mihai Eminescu. What is dreadful, in my opinion, is the sensational avidity, which generated long talk shows about the insanity of the poet, not about his masterpieces. Only some true lovers of his works still remain, and they are those who celebrate him with genuine respect and consideration. Officially, January 15 is a day when a handful people from the cultural/educational sphere organize events – arguably more or less boring, flat and conventional- and when those who know and love Eminescu's work silently celebrate him by re-reading his works.

In contrast, the national poet of the Scots has been celebrated for more two hundred years (from 1803 in his birth place in Ayrshire) with love, passion, respect and nostalgia at the annual Burns Supper. At the Burns Supper, Scots from all the world gather, wearing their traditional kilts and tartans and evoke Burns’ life and masterpieces, listen to Scottish music (mostly with Burns’ verses), dance their traditional and unmistakeable dances, eat the unique - and challenging for foreigners- haggis which is usually brought in by the cook, while the piper plays bagpipes and of course they drink whiskey. For the Scots, the Burns Supper is like a second national day after Saint Andrew's on November 30. It is a day of celebrating their deep, dramatic and special passionate soul. The Burns’ day is the day of Scottish’s soul. The Burns’ poems as “The red, red rose”, “Auld Lang Syne” (sung on Hogmanay, the last day of the year) , “Tom O’Shanter”, “Ae fond Kiss”, “Address to a haggis” or “Scots Wha Hae” (a long time the unofficial national anthem) are known not only to all Scots natives but to many poetry lovers from all over the world.

By contrast, in Romania a lot of people don't know anything about the country's national poet. If we were to survey this topic, we would sadly find that mostly elder people still know poems written by Eminescu. The heydays when Eminescu was an idol for young people, for patriots or only for sensitive people are now gone. Now new idols are in fashion. Maybe few of the so called “proud Romanians” would be angry with me and they could say that my comparison with Scottish is dissonant. Their arguments could be the history, the language in which the poems were written or the power of international lobby. But I believe I can answer all of these challenges.

Firstly, the historical argument which says that Scotland is an important part of a great country, a huge empire, it can be interpreted in another and more adequate way. Scotland is a region of the United Kingdom but this argument is at least simplistic. Along its history, Scotland has had a lot of problems with England and the integration into the British Empire, as the Scottish anthem “The flower of Scotland” or the famous battles from Bannockburn (1314) to Culloden (1745) tell us. The integration into the British Empire is a problem even today when the independence of Scotland is a very present topic.

Secondly, the linguistic argument is superfluous because many of Burns’ poems are written not only in English, but in Scots language and also in Scottish English dialect. The Scots language is of loosely Germanic origin and was spoken in Lowland Scotland (the south of the country) and in Ulster (in North Ireland). It is different to Scottish Gaelic, which belongs to the Celtic language group and is spoken in the Highlands. Burns' Scottish English is a variety of English spoken in Scotland which, according to the linguists, may or may not be considered distinct from the Scots Language. Whatever the verdict, the Scots Language and the Scottish English dialect are clearly distinct from the Scottish Gaelic spoken in Western Highlands and Isles.

Thirdly, the powerful lobby could be a good argument but it seems to be born not of any particular organized group, but rather to spring from the love Scots and those of Scottish descent have for the misty, rainy, faraway native country.

The very different ways to celebrate these two national poets perhaps reflect differences in the emotional connections the two peoples have to their native countries . Some Romanians - including those who really love their country - have the complex of the affiliation to a small country with a periphery culture. The Scots, in spite of being few in number (five million in Scotland and some 40 million all over the world) are proud to be Scots. This pride and the faithful love for their history, culture and traditions has helped us Romanians, and other nations in the world, learn a few things about Scotland, even if some of them are already cliches: whiskey, rugby, kilts, haggis, Loch Ness monster, Sherlock Holmes, Dr.Jekyll and Mr.Hyde, Mary Queen of Scots, William Wallace, Andrew Carnegie, David Hume, Adam Smith, Alexander Fleming, Sean Connery, Andy Murray, Rangers, Celtic...so on...so on.

When we Romanians celebrate with respect our national poet and name him “Mihaita” with a honeyed word as the Scots say “Robbie” or “Rabbie” to their poet or when we build a Memorial for him as the one for Burns in his native village Alloway (Ayrshire area), then we'll be more able to design a true, valuable country brand and we’ll not need any leaf or leaflet to define the so called Carpathian garden. We could tell the world much more about our precious Romanians such as Mircea Eliade, Eugen Ionescu, George Enescu, Constantin Brancusi, Tristan Tzara, Henry Coanda, Dimitrie Cantemir. Everyone had good and bad characters in their history, but we, Romanians, seem to love to promote the bad ones! We could create a true country brand by loving, respecting and promoting the true Romanian soul, and we could take some inspiration from the Scots to do so. Is it not time to let the world know there's more to us than Nicolae Ceausescu and Vlad the Impaler?

By Mariana Ganea, Guest Writer