Theater in times of confinement: How a play about the Romanian Revolution of 1989 turned into a Zoom production in U.S.

As theaters were forced to close their doors because of the coronavirus pandemic, British playwright Caryl Churchill’s 1990 play Mad Forest, about the Romanian Revolution of 1989, was turned into a Zoom livestream performed by acting students from the Bard College Theater & Performance Program.

Romania-Insider.com has talked to director Ashley Tata about how live performance and video technology blended in the making of the complex production, the adjustments made in switching from a stage version to a Zoom one, and the particularities of the hybrid video - drama format.

In the spring of 1990, Caryl Churchill, theater director Mark Wing-Davey, and a group of students from London’s Central School of Speech and Drama traveled to Bucharest to see what was happening in the country. While in Bucharest, they worked with Romanian acting students to develop the play and conducted various interviews. Within two months of their return to England, the play was in production.

Mad Forest: A Play from Romania directed by Mark Wing-Davey premiered at Central School by the summer of 1990. The same year, Romanian director Andrei Șerban invited Mad Forest to Romania, where it was performed at the National Theater in Bucharest, in September. It was later performed at London’s Royal Court Theater, in October 1990. In the U.S., it opened at New York Theater Workshop a year later, with a cast of professional actors.

The three acts of the play take place before, during and shortly after the 1989 Revolution, focusing on two Romanian families, the testimonies of those who experienced it, as well as the period that followed, when conflicting views on the events of December 1989 emerge, and people start to question the idea of the revolution.

Thirty years after Churchill’s trip to Romania, acting students in the Bard Theater & Performance Program, directed by Ashley Tata, started working on a stage production of the play, which they planned on performing at the Fisher Center for the Performing Arts at Bard, in New York. The coronavirus pandemic led to the cancellation of the performance, so they decided to move the production online for a Zoom-formatted version, co-presented by the Theater for a New Audience.

When the production was moved online, the cast had already been rehearsing for the stage version. “We had staged all of Act I before we had to leave campus and we had done a pass at Act II, but we reorganized that for being online, and we had staged most of Act III, but we didn’t do the last scene in Act III at all; we hadn’t even touched the last scene with the fight. So that was completely staged online,” Tata recalls.

She believes that having begun work on the production on stage helped, at least in part, the Zoom work process. Some of the actors had known each other for several years, and the director had worked with several of the designers involved in the production before.

“I talked to them a lot about having to actively engage their imaginations and make their scene partner be in a room with them. Just off-camera.” At the same time, having the reference point to what they had done in the room was useful for the actors’ physical orientation. “I would say ‘Remember when we were rehearsing before that actor was on your right, so just put them stage right.’ It’s the same idea.”

The webcast saw the twelve students perform live from locations across the United States, with the help of a modified version of Zoom developed by programmer Andy Carluccio. He created a modified version of the software to enhance its visual and storytelling abilities and allow for camera editing in real-time. Eamonn Farrell, the video designer, ran the custom Zoom feed through Isadora, a video design software, while designer Afsoon Pajoufar created around 125 individually designed virtual backgrounds against which students would green screen themselves. The student actors were sent green screens, lighting equipment, Bluetooth earbuds, props and costume pieces, and hardwired internet connections when needed.

The actors, the director, and the stage manager were all in a Zoom call, broadcast out through Isadora. The stage manager was there to give the actors cues when necessary, while the director would send the actors feedback from the comment section. It helped actors feel like the audience was part of their world, Tata explains.

When switching to a Zoom version, one of the big adjustments made was to the scenic design. In the stage version, each act had a different look, with a design that “expressed something psychologically about the space and revealed something about the psychology of the characters.” In the Zoom version, everything turned two-dimensional. An initial idea was to take the stage rendering of the real-life production and create backdrops with that. “But it became clear that that would just be confusing, and it wouldn’t help tell the story. So she had to go about it in a more filmic kind of way […], but we were able to maintain overarching aesthetic ideas. In the first act, things are a bit more sickly in color, and in the second act, we go into this kind of black-and-white documentary style. The third act is brightly colored. That was an idea that transferred from the real-life production to the virtual production,” Tata explains.

The director believes the second act, which presents testimonies of the Revolution, “was surprisingly stronger than I had hoped it would be,” something she attributes to “the intimacy that Zoom allows, that direct camera confessional kind of mode.” Using the Zoom platform also allowed for various film games or tricks, like a hug between two characters.

When working on the production, Tata also looked at how television was a conveyor of the message of the Revolution, something that transferred into the aesthetic of the production, from various filters to incorporating potential tech problems. The actors also received texts on the effects of the television and the revolution. “I think it is a fascinating subject and continues to today when we have our iPhones with us all the time.”

Using the platform was not without its challenges. In one instance, it completely crashed, and the team had to restart the broadcast. The night before the production opened for the Theater for a New Audience run, a Zoom updated nearly changed the workflow. “Thursday night, after our dress rehearsal, the coder told us ‘Zoom might update tonight, and we’ll know at 3 in the morning whether the code works or not’ […] We would have had to manually spotlight, do it without the code, we could have pulled it off, but it would have been really bumpy.”

Over 4,000 people tuned in from countries all over the world for the online version of the play, including the U.K., Ghana, Vietnam, Romania, and from across the U.S.

Those who tuned in were able to comment on the play in the chat section, where members of the production team would also answer questions. “The interesting thing about having the comments section open and people participating in it was that a number of times people spoke about feeling like they were in a theater space with other people […] I think that’s really exciting as far as creating a sense of community,” she explains.

When asked about how the play resonates with today’s audience, the director says she was interested in how it raises questions of responsibility. “What is interesting about the writing of this piece is that it doesn’t seem to end with ‘there is a Revolution, and then everything is restored, and people have their rights restored, and it’s like a happy ending.’ It’s something about responsibility. If a people do take something on, there is also a responsibility that comes afterward or a kind of follow-through in a way.”

At the same time, Churchill’s play is “a fantastic ensemble work. It’s a piece that was written for young performers. So there are practical reasons why it worked for a group of students,” she says. “There is something about the structure and how it was made that I feel that younger performers bring life to it in a way that maybe a more refined performance wouldn’t be as successful.”

And, it lent itself well to the Zoom format. “If we were doing Orestes, I don’t think we would have moved that to Zoom. Even though it is a great play and it is a great play for this time, the choral issue, in particular, would be very difficult.” She sees Shakespeare’s Romeo and Juliet potentially working in a Zoom format, Chekhov’s Cherry Orchard, or a S.F. piece, like a short story by Ray Bradbury, or a piece written specifically for this format. “Zoom changes the architecture of theatrical space, so there could be plays that flag that accordingly.”

But beyond the need to adapt to the closure of theaters, Zoom-formatted productions can stand on their own. “My continued goal about getting any of these things out there is to try to offer to an audience and producers that this could be a viable form of theater for right now […] I’m hoping that we can still make work somehow and I hope that audiences would be interested in that work until we are able to get back into a room together.”

Mad Forest was originally presented by Upstreaming: the Fisher Center at Bard’s Virtual Stage. Three additional performances were presented between May 22 and May 27 in coproduction with the Theater for a New Audience.

Cast: Phil Carroll, Andrew Omar Crisol, Lily Goldman, Tim Halvorsen, Mica Hastings, Azalea Hudson, Ali Kane, Gavin McKenzie, Taty Rozetta, Violet Savage, Yibin (Bill) Wang, Charlie Wood

Creative team: Afsoon Pajoufar (Scenic Design), Ásta Bennie Hostetter (Costume Design), Abigail Hoke-Brady (Lighting Design), Paul Pinto (Compositions and Sound Design), Dan Safer (Movement Direction), Eamonn Farrell (Video Design), Vanessa C. Hart (Production Stage Manager), Andy Carluccio (Video Programming), Sean B. Leo (Video Engineer), Shane Crittenden (Properties Master), Anisha Hosangady (Assistant Stage Manager), Maggie McFarland (Assistant Stage Manager/Sound Operator), Laila Perlman (Assistant Director), Angela Woodack (Assistant Director)

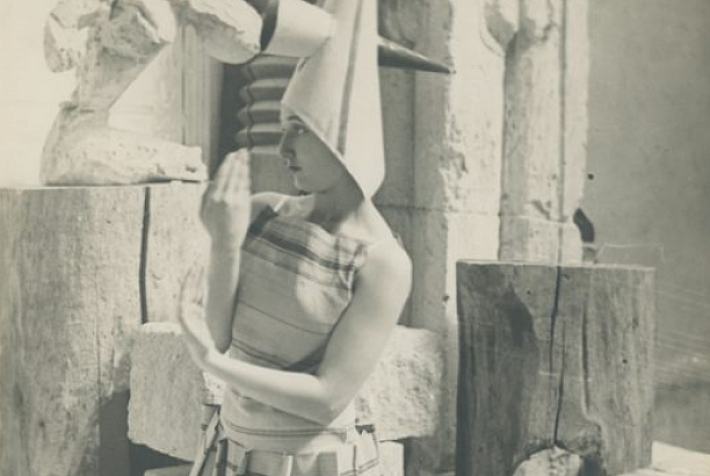

(Photo: Bard College Facebook Page)

simona@romania-insider.com